As a parent, having watched my kids do various part-time jobs on minimum wage, I’ve seen how fragile “flexibility” can be. Yes, they are young, but they still have rent and bills to pay. More than once, I’ve watched their employers expect them to turn up at a moment’s notice, only to be sent home again because it’s quieter than expected. The joy of the zero-hours contract.

Formalised in 1996 by the then Conservative government to improve worker protections and no doubt to increase the tax take, though I’ve never seen that admitted officially. There had always been a casual workforce, but this enshrined the relationship between those employers and employees in law for the first time.

The world of work had been changing rapidly since the early 1980s. Zero-hour contracts were seen as a potential solution for a casual workforce, offering flexibility for different industries and different types of workers. At least in theory, it was a win-win solution for the modern age.

Casual and on-call labour has been around for a long time as informal work, often used in ports, agriculture and hospitality. The Employment Rights Act 1996 allowed contracts with no guaranteed hours. Initially, it wasn’t widely used, certainly not outside hospitality, retail or care. But in 2008, the financial crash happened, and this is when employers started to pass the risk of business volatility on to the employee through a much wider use of these contracts. They became part of the cost control tools of business rather than the flexibility tool they were intended to be. As public outcry rose with the increased numbers of these contracts, the government in 2015 banned exclusivity clauses.

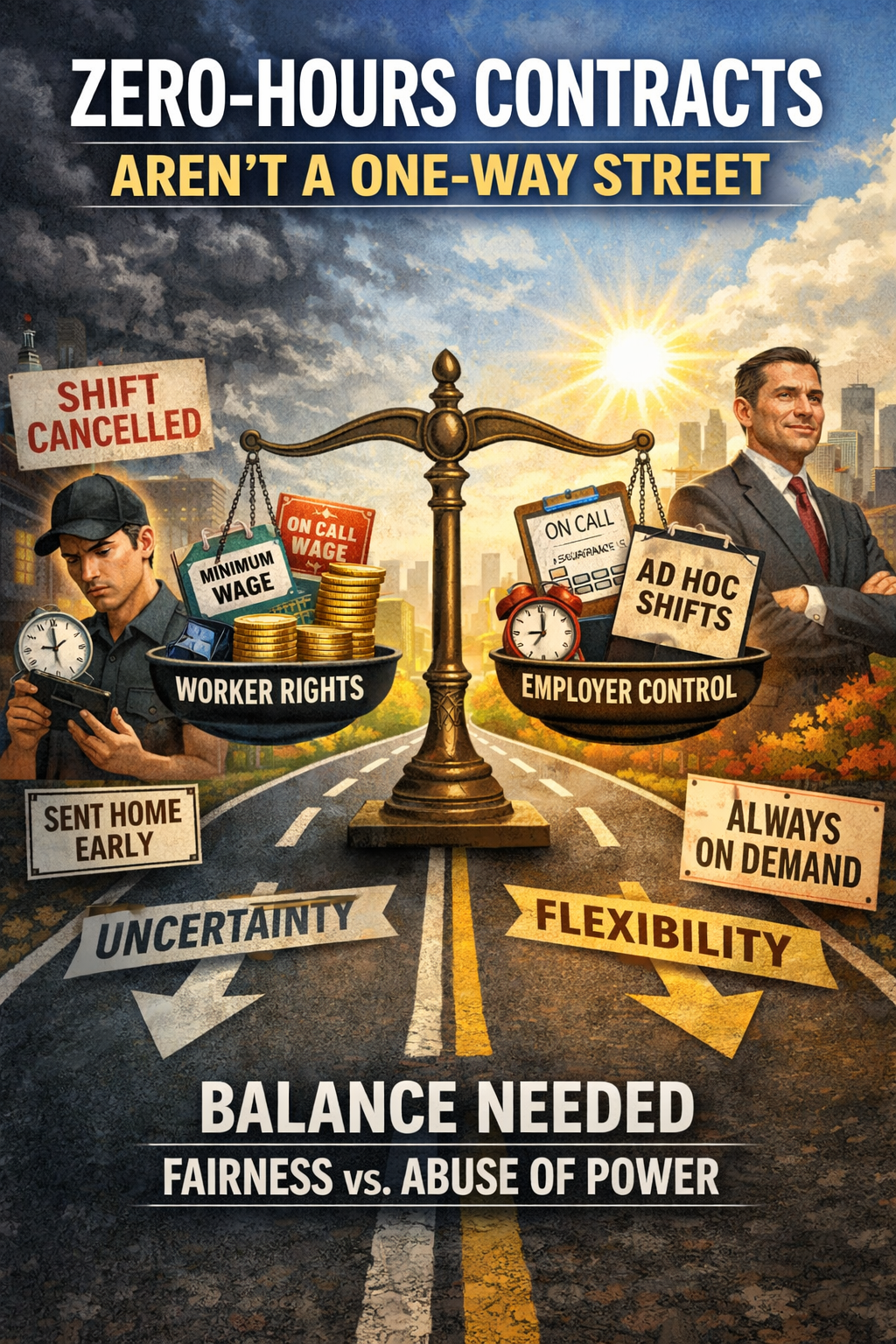

So, while the cultural assumption is that zero hours are exploitation, that wasn’t the original intention, but it is how they have often become. However, as with most assumptions, it’s a little more nuanced than that. Much of the anger comes from a misunderstanding of what the rules are, businesses relying on that misunderstanding and guidelines being largely ignored, as they are well, just guidelines.

While the flexibility was meant to work both ways, the reality is that

- Some employers treat zero-hours employees as an on-call workforce

- Give the impression that an offered shift isn’t an optional shift

- If a worker declines a shift, the inference of less future shifts often scares the employee into accepting a shift they don’t really want

- Sending employees home when a shift is quiet, taking the onus of planning appropriately away from the employer

- Zero hours contracts are used where an employee is needed every week, which under the guidelines a low hour’s contract would be more appropriate

- Rely on the employee not fully understanding their rights

Zero hours contracts should be a mutual agreement between employer and employee. If work is available and offered to the employee, they should be able to accept it or not. If the employer doesn’t find this acceptable, then their employee is probably on the wrong type of contract. Government guidelines suggest that if you require an employee to work every week, then they probably shouldn’t be on a zero-hour contract. The problem is that this is a guideline. Where an employer genuinely can’t guarantee hours or an employee’s availability is sporadic; they are a great tool that can benefit both sides of this working relationship. There is nothing to stop an employer from having a dozen such people on this type of contract, ensuring they always get the shifts filled, and nothing to stop an employee using that to their advantage and having several zero-hour contracts.

With that in mind, coming into the end of the Xmas period and “dry January” in more ways than one, here is a list of what every employee should know.

- You can legally decline any shift – and you cannot be punished for doing so

- Exclusivity clauses are illegal – you are free to work multiple contracts

- If you’re called in and sent home, you may still be entitled to pay, depending on your contract

- You decide your availability, not your employer

- You are entitled to minimum wage, holiday pay and rest breaks, just like any other worker

- Employers cannot cut your hours as a form of punishment

- You can challenge misuse through ACAS

- Most importantly, read and understand your contract

As an employer, you have rights too, but you are the one in the position of perceived power. If you need at least X hours a week from someone, consider writing that into their contract and share the risk and uncertainty. That, after all, was the balance zero-hours contracts were supposed to strike in the first place.

It’s worth noting that there are some changes afoot. Later this year, clarifications to the Workers (Predictable Terms and Conditions) Act 2023 will come into force. While some of the detail is still being worked through in Parliament, the direction of travel is clear: flexibility is meant to work both ways, an ingredient that has been quietly ignored in these contracts for years.

It will give workers the right to predictable working patterns after a 26-week period of service. This includes predictable hours, days, times and the length of contract. Employers will have to make a very good business case to turn down any requests of this nature. How this will be policed remains to be seen, but it’s encouraging that the government has recognised and is attempting to address a major flaw in these contracts. What the new legislation won’t do is guarantee fixed hours, ban zero hours contracts or stop the opportunity of flexible working patterns for those who still want them.

Agency workers are to get the same rights. If an employer refuses unreasonably, the worker can challenge it. It’s not perfect, and it won’t fix every situation, but it is a recognition that the system has tilted too far in favour of employers and that the original purpose of zero-hours contracts needs restoring.

Zero hours contracts aren’t inherently good or bad; they are a tool that used as intended can benefit both sides of this equation. The debate often overlooks this point, only seeing the harm from misuse while ignoring the intent of worker protection.

Zero-hours contracts aren’t a one-way street, but too many employers act as if they are. It’s time to put the balance back and hopefully the new legislation is a step in the right direction.

For more details on that legislation, you can find an overview here.

Leave a comment