How the UK–US pharmaceuticals deal shifts costs onto the NHS

I’m writing this partly out of surprise. Not because the deal itself is automatically indefensible, but because it was agreed by a Labour government. At first glance, it feels counter-intuitive, not in economic terms, but in political ones.

This is not an anti-Labour rant. Nor is it an argument against free trade, cooperation with the United States, or investment in pharmaceutical innovation. In isolation, none of those things are objectionable. The point here is simpler, and more uncomfortable: this deal does not do what the headline suggests, and its costs fall in a place that many Labour voters would not expect.

What follows is an examination of trade-offs rather than ideology. Specifically, how a policy presented as a free-trade win quietly shifts long-term costs onto the National Health Service, and what that tells us about how modern governments, including the Labour Party, now balance public services, markets, and corporate interests. The other challenging aspect of this deal is the gap between its rhetoric and its actual substance. There are links to both below.

If the Conservatives had agreed to the same terms, the substance of this critique would be identical, just less surprising.

The phrase “Zero Tariffs on UK pharma” sounds like a clear win for UK – US trade. It immediately makes you think of cheaper drugs, lower costs and, by extension, better patient outcomes. It sounds like a win-win, and that is precisely how it’s meant to sound. The press release positively gushes. Yet, closer inspection tells a more complicated story, not that it’s a “bad” deal, just not what we are being presented with.

The trade agreement itself is called “The UK-US Economic Prosperity Deal”. It barely touches on medicines or pharmaceuticals, and even when it does, it is about the intention to negotiate. There is no mention of the NHS, NICE or even pricing thresholds. It definitely does not mention patient costs, and the press release offers no link to the documents for the updated deal. A charitable reading is that the political announcement has run ahead of the final wording of the deal itself, and that the detail will follow in due course. I am prepared to assume that is the case.

However, that still doesn’t alter the central issue. The real substance of this announcement is not within the trade deal itself, but that it sits with domestic UK policy changes. Changes that will cost the NHS money. These costs arise because of NICE methodology reforms, including a roughly 25% increase in what the system is willing to pay for medicines, along with cost effectiveness thresholds raised to allow greater access to innovative drugs.

But this threshold will apply to all drugs, not just innovative treatments. This creates the potential for higher prices, not just for new drugs but for existing treatments already in use. Alongside this, the government has committed to a more ‘stable and predictable’ pricing and rebate environment. This is something the pharmaceutical industry has long argued for. What it means is less money flowing back to the Treasury and a higher net cost to the NHS.

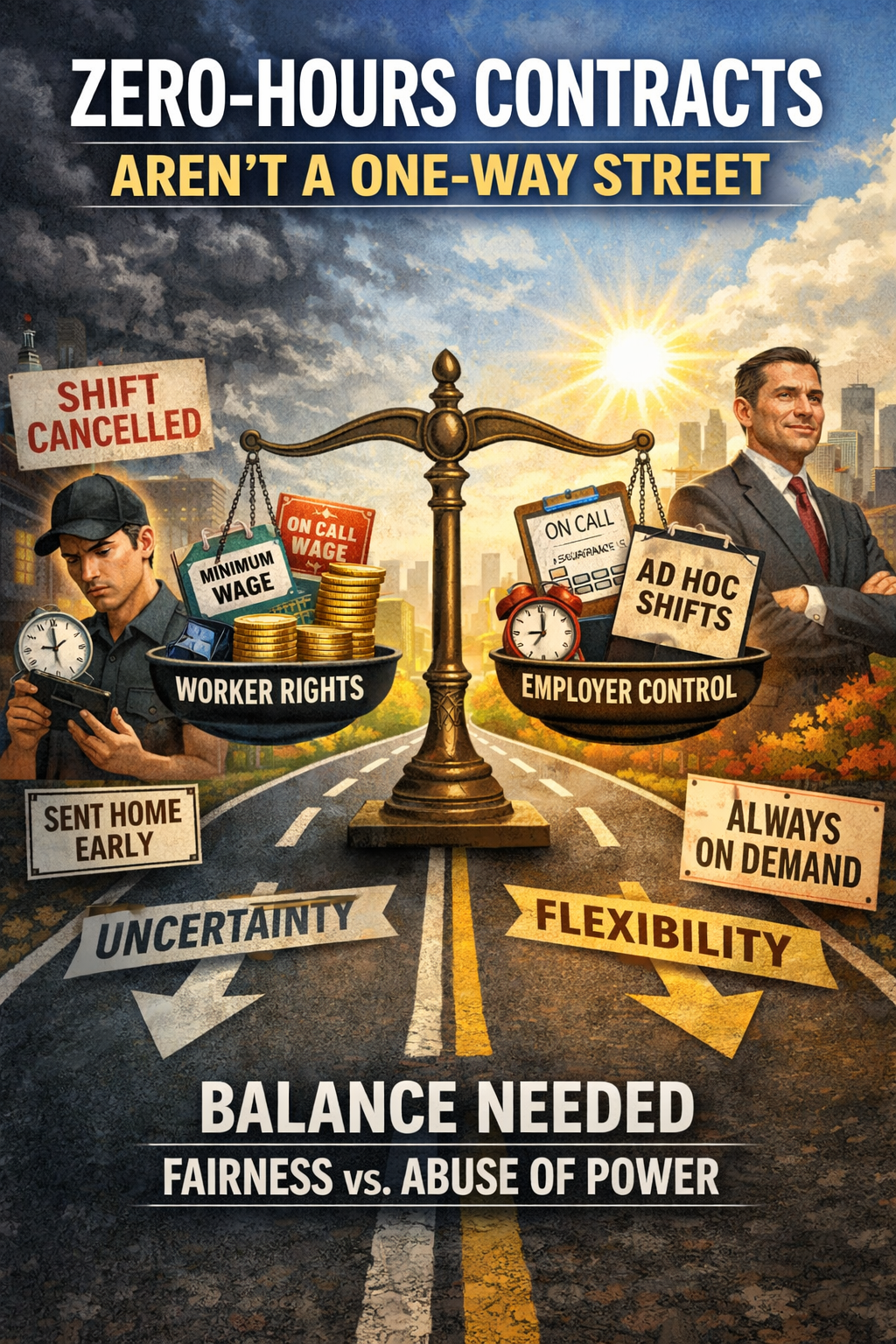

This is where my surprise lies. This is a trade deal in which the deliberate trade-off is tariff relief for industry at a cost to a public service. It does deliver greater access to innovation and a broader range of medicines, but at a higher price. Paying more may bring benefits, but those benefits come with both a direct financial cost and an opportunity cost elsewhere in the health system.

The principal beneficiaries of this deal appear to be pharmaceutical companies, UK life sciences exporters, and their investors. That is not inherently problematic, but it matters when set against how the policy has been presented. The government has framed the agreement as one that primarily benefits patients and the NHS, yet that does not appear to be the case.

Any additional costs will ultimately be borne by NHS budgets and, in time, by taxpayers, even before accounting for the opportunity costs that accompany higher spending in one part of the health system. Framed this way, the deal looks less like a patient-centred reform and more like an industrial policy choice, one that prioritises large corporate interests over the cost discipline of a publicly funded service.

There may be nothing inherently wrong with that, depending on one’s perspective. But it is an unusual policy choice for what I’d traditionally recognise as the Labour Party.

The modern Labour Party has moved on from its roots. It is now broadly pro-industry, pro-globalisation, and pro-free trade. When pharmaceutical companies are framed as “innovation” in the press release, rather than as concentrations of corporate power, it reflects a careful choice of language. The framing is designed to sit comfortably with Labour’s traditional voter base, even as the substance of the policy aligns more closely with a pro-industry, market-oriented approach.

Likewise, when the NHS is treated as a negotiable lever within wider economic strategy, and growth is prioritised over the cost discipline of public services, it suggests a party operating in a far more market-liberal space than that traditionally associated with the left. It is this sleight of hand that allows them to be more open to business, while still appealing to their voter base.

So while UK corporations gain improved access to American markets, and American corporations secure better access to the NHS, the costs of free trade are borne by the very people we are told it is meant to benefit. This is not a sell-out of the NHS, nor a betrayal of public services; it is a policy choice.

But it is a policy choice that should be presented honestly. In this case, free trade will not make medicines cheaper for the NHS. I’m comfortable with that trade-off in principle; I’m simply surprised by the party that chose to make it.

You can find links to the Press release here and the trade document here.

Leave a comment