Stop Taxing Subsistence: Rethinking the Personal Allowance

A few weeks ago, there was a flurry of media noise around Reform’s proposal to raise the personal allowance to £20,000. There was very little detail behind it, but the usual suspects were wheeled out, and the same old models were used to explain why it would be a fiscal disaster. Given that Reform was also proposing to raise the 40% threshold to £70,000, that criticism may well be fair. However, I don’t think the underlying idea has to be. What follows is not a defence of Reform’s policy, but a proposal for how a £20k tax-free floor could be designed as a genuine redistribution, with meaningful side effects, at a limited net cost.

In a Facebook discussion, I suggested that such a policy could be broadly self-funding, and I was called out on that. The challenge was fair on the wording, but I don’t think the idea deserves to be dismissed with “the model says no.” As I’ve argued in a previous blog, the economic models we lean on were built to solve the problems of their time and they are also the models that have helped shape the world, for better and for worse.

It’s time to do things differently…

People are struggling across the country with the cost of living. That pressure has a long tail of negative effects — on health, crime, addiction, and poverty. I think we can all agree these are not outcomes we should accept as the normal price of running an economy.

£20,000 is the figure that’s been bandied about, but it could just as easily be £18,000 or £22,000. It might even vary by location. The real question isn’t the exact number; it’s the principle. Should we be taxing subsistence living at all? If you need your income simply to survive, is it reasonable for the state to take a slice of it? I’d argue it isn’t.

If we were serious about this, we’d anchor the tax-free floor to a measure of minimum living costs. For the sake of this discussion, I’m going to assume that floor sits at £20,000.

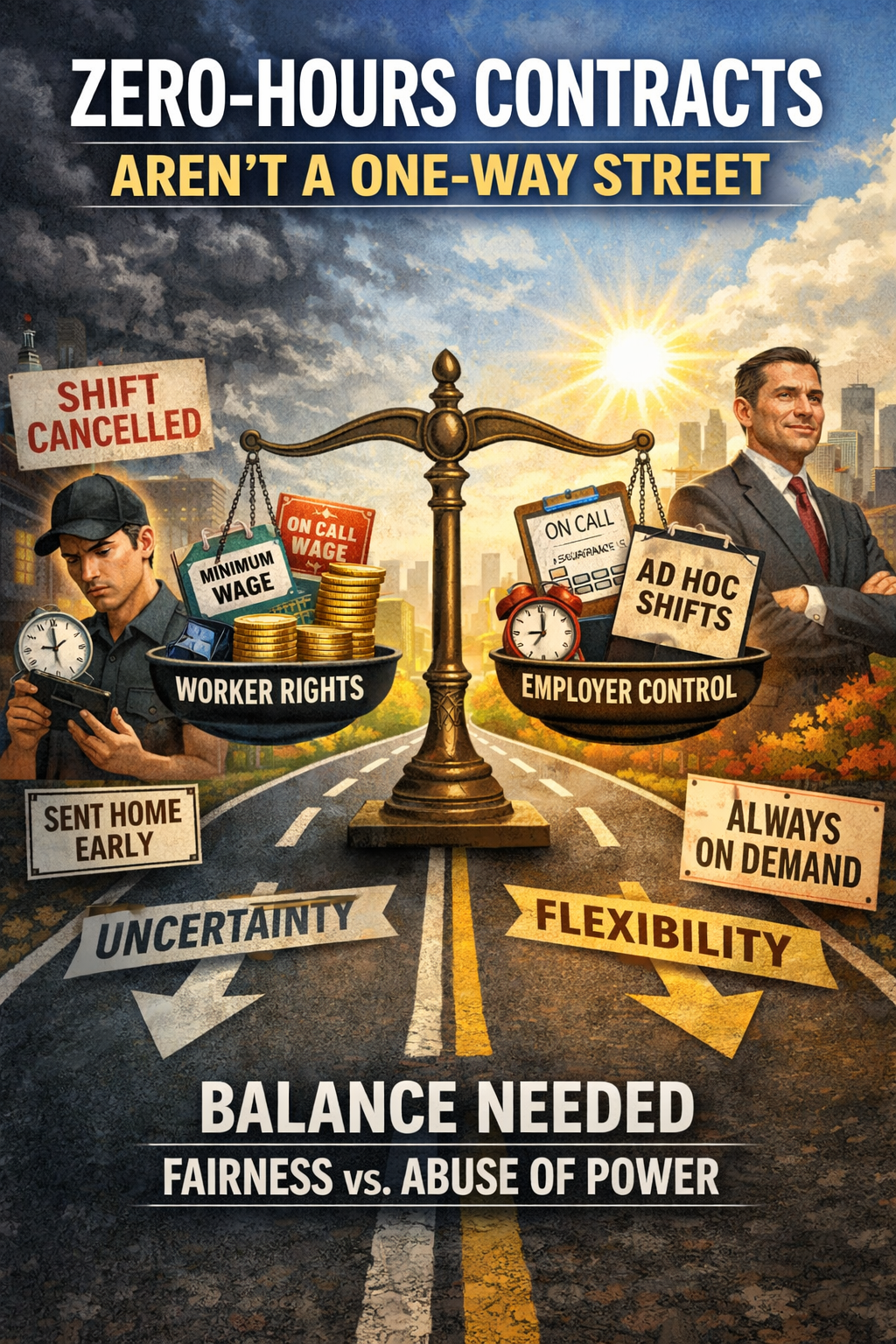

When the personal allowance changes, the standard approach is to keep the width of the other tax bands the same. What sounds like a progressive reform on the surface often turns into something much less so in practice, because it pushes the higher-rate threshold up at the same time. That both increases the overall cost of the policy and hands a disproportionate benefit to higher earners.

For example, take someone earning £60,000:

Before

Taxable income = £60,000 − £12,570 = £47,430

Tax:

- £37,700 @ 20%

- £9,730 @ 40%

After (PA = £20,000, bands move as usual)

Taxable income = £60,000 − £20,000 = £40,000

Tax:

- £37,700 @ 20%

- £2,300 @ 40%

What’s happened here is that by raising the personal allowance while keeping the width of the bands fixed, income that was previously taxed at 40% has been shifted into the 20% band. The result is that higher-rate taxpayers gain more per pound of allowance than basic-rate taxpayers. Quite the opposite of what most people imagine when they hear “raise the personal allowance.”

This design choice is at the heart of much of the criticism levelled at proposals to raise the allowance. But it’s just that: a design choice. The Scottish Government has already shown that tax bands don’t have to move in lockstep with the personal allowance.

What I would propose instead is simple: raise the personal allowance to £20,000, but do not allow the upper bands to move with it. In other words, the 40% and 45% thresholds remain where they are. This removes much of the windfall effect for higher earners and ensures the redistribution actually targets the people it’s meant to help.

I’d go further. A single national floor ignores the reality that the cost of living varies wildly across the UK. A region-adjusted tax-free floor would be economically cleaner and more honest. We already have the administrative machinery to do this: HMRC applies different tax codes for Scotland and Wales today, and payroll systems handle it without drama. Extending that logic to regional floors isn’t a technical challenge; it’s a policy choice.

I have come to this figure by taking the working population and multiplying it by the lost tax at the 20% rate. So, while it potentially overestimates that cost, as not all the 32 million working population are hitting that threshold, so wouldn’t be paying that tax under those circumstances. I feel it is a more honest approach. It differs from other models that you will see, as those models consider the shifting bands.

The static cost of this policy is large; I’m not pretending otherwise. My rough estimate puts it at around £45 billion per year. I arrived at this figure by taking the working population and multiplying it by the tax foregone at the basic 20% rate on the additional tax-free allowance.

This is a deliberately blunt calculation. It likely overstates the true static cost, because not everyone in the roughly 32 million strong workforce earns enough to make full use of a £20,000 allowance, and many would only benefit partially. I’m comfortable with that. I’d rather err on the side of overestimating the cost than understating it.

This approach also differs from much of the modelling you’ll see in public debate, which often assumes the tax bands move up with the personal allowance. That design choice materially increases the headline cost and is not what I am proposing here.

In my view, there are three main channels through which a significant portion of the cost of this change could be met:

- Increases to the headline tax rates on existing bands

- Macro feedback from putting more money into people’s pockets

- Structural effects (labour supply, benefit churn, and wider societal gains)

I’ll take these in turn and build up a picture of how much of the headline cost could plausibly be covered.

Tax rises

Tax rises are never popular, but context matters. A one percentage point increase on each of the three main income tax bands, in return for lifting the personal allowance to £20,000, is the kind of trade-off many people would accept: a small, broad-based contribution in exchange for a large, visible improvement in take-home pay at the bottom end.

Using HMRC’s Direct effects of illustrative tax changes (June 2025), a 1p rise on each band raises on the order of £9–11 billion per year. That still leaves around £35 billion of the original static cost to account for, but it also shows that a meaningful chunk of the funding can come from a relatively modest, widely shared increase in rates.

Macro Feedback

The OBR’s central estimate for the multiplier on tax cuts is around 1.4. In plain terms, that means £1 of tax cut is estimated to generate about £1.40 of additional economic activity as the money circulates through the economy. That effect is not immediate; it occurs over time, typically tapering over a five-year period.

importantly, that 1.4 figure reflects average tax cuts applied broadly across the income distribution. The proposal set out above is deliberately targeted at people with a high marginal propensity to consume (MPC), those who are likely to spend most of any additional income simply because they need to. For that reason, I think it’s reasonable to assume a higher effective multiplier. I’ll use 1.5 here, which is in line with the lower end of the range often used for direct government spending.

That still isn’t a crazy assumption far removed from the likes of the OBR or IFS modelling. If anything, it’s cautious. Government spending multipliers are often higher precisely because the money goes straight into demand, but public spending is also notoriously inefficient at times. I’m not assuming this policy outperforms direct spending, just that it’s in the same ballpark.

If we apply a 1.5 multiplier to the remaining £35 billion of net fiscal impulse (after the 1p rate rises), that implies around £52.5 billion of additional GDP once the effect has fully worked through the economy.

With tax receipts running at roughly 38% of GDP, that translates into about £20 billion in additional revenue returning to the Treasury in steady state (albeit phased in over several years). At that point, roughly two-thirds of the original £45 billion static cost has been covered through a combination of explicit tax rises and macroeconomic feedback.

Structural Effects

For me, this policy doesn’t sell itself on the claim that it “pays for itself”. Even if some of the cost does come back over time. It sells itself on what it does to the fabric of everyday life for people who are under constant financial pressure.

For someone with a spare £30 a week, an extra £30 doesn’t change much. For someone who doesn’t have that margin, it can be the difference between living a constant low-level crisis and having a little breathing room. Not life-changing in the dramatic sense, but life-stabilising.

That kind of stability has knock-on effects that are hard to capture neatly in fiscal models:

- Labour supply – this is exactly the sort of incentive that could move people to work more hours. Less financial stress means less downtime from illness, greater productivity and a happier worker.

- Benefits churn – higher take home pay reduces reliance on in work benefits. What this really targets are the marginal rate of return when coming off benefits, which currently sits at around 81p in every £1 earned above the credit limit.

- Mental and general health – removing stress, worry and financial pressures will have knock-on effects for health of all kinds. Over time this should reduce long-term costs for the NHS.

- Crime and coping behaviours – When people don’t cope, they look for ways escape pressure. That can be from drugs, alcohol or crime. Removing some of those pressures reduces the impact these behaviours have on society.

- Family stability and child outcomes – less stress at home tends to lead to better outcomes away from home. We talk a lot about child poverty; this could have a meaningful impact on it. This is where many of societies long term costs originate and this would be a start to nipping some of that in the bud.

Of course, none of the above is guaranteed, despite being tenuously linked to death and taxes. They are not easy to quantify in economic modelling or treasury spreadsheets. What we do know is we already deal with the consequences and not insignificant associated costs. Even if these structural effects fund none of this policy, at the residual cost of £10-15 billion, I’d still argue that, in the scheme of UK government budgets, it would be money well spent.

None of these arguments fit neatly into the current models and scoring methods, that isn’t what they’re designed to do. They are built to assess changes within existing systems, and throwing structural redesign and behavioural effects at them is, to some extent, unfair. That doesn’t mean these effects can’t be modelled; just that the current analysis generally isn’t set up to do so, though it could be.

So, is this a fully self-funding tax break? It might be…. but probably not, at least not within the timeframes these things are usually measured. The impacts of behavioural change and structural shifts are slow to show up in the data, and it may take years before the full effects are felt.

Does that mean this isn’t worth doing?

I’d argue the real question is this: in the current climate, can we afford not to?

Leave a comment