We live in a time where the current orthodoxy appears to be the only one presented to us, at least in economics. This has led to a position where the media claims “Economists Say…” as though they are one body of thought. Nothing could be further from the truth. If you were to ask 10 economists for the solution to an economic problem, you’d get at least 11 different models.

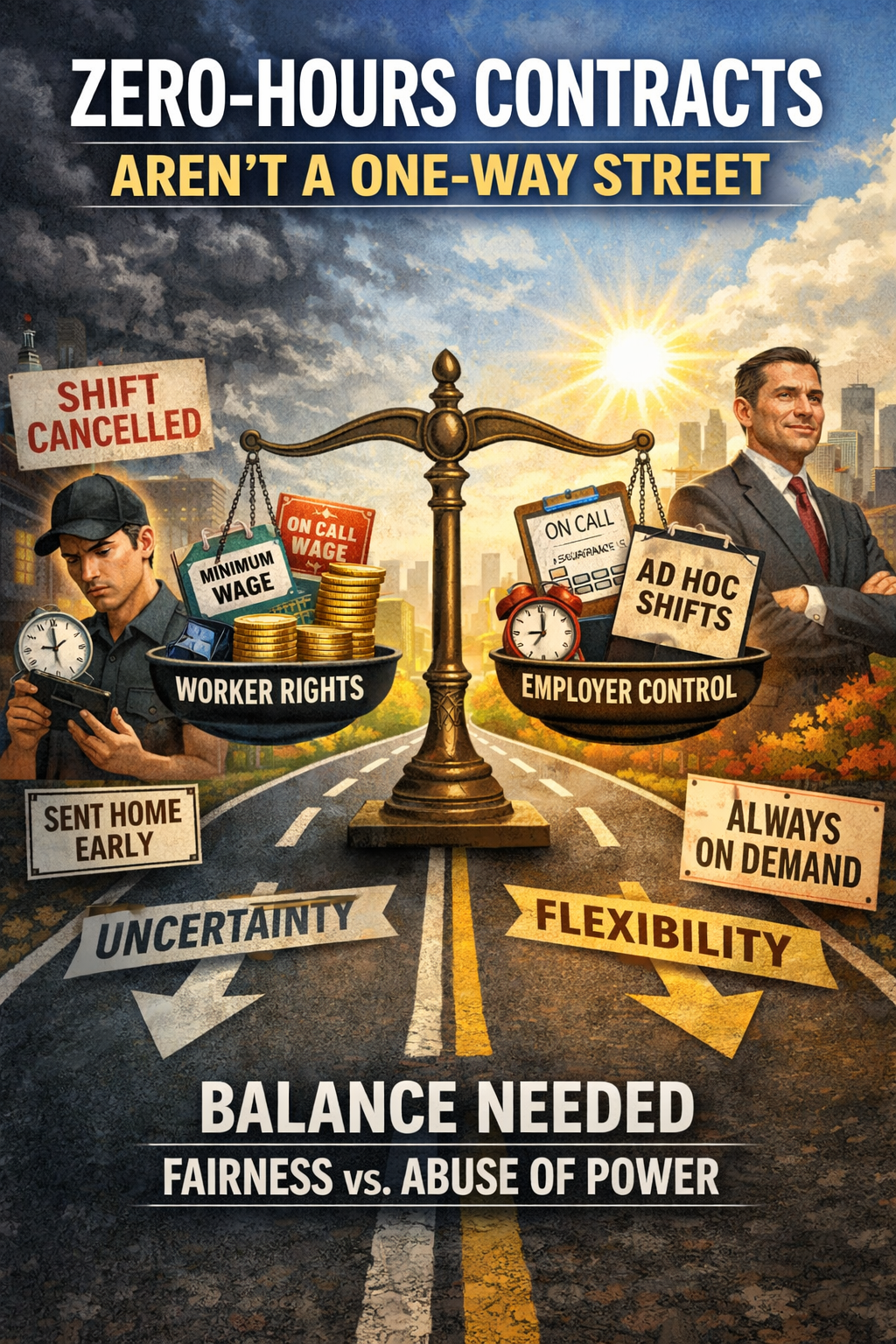

Most schools of economic thought sit between two main policy approaches. These are framed by the two main government levers in economics, “fiscal” and “monetary” policy. At one end of the line, you have fiscal policy, which relies on government spending, taxation and investment, the other, monetary policy, which focuses on interest rates, money supply and inflation targeting. My one take from both these positions has always been;

Fiscal – where the government gets to decide how many of us get to keep a job

Monetary – where the Bank of England gets to decide how many of us get to keep a job

Both can keep inflation down, both can overshoot, and both have very real human consequences. The media never explains this; they just trot out today’s economist, and everyone assumes it’s a consensus view. What everyone needs to understand is that Economics isn’t a science in the way physics is. It’s a debate. A series of models, assumptions, and competing worldviews.

Beyond these two policy levers, economics is split into multiple schools of thought; some overlap a little, some contradict each other and some build on earlier ideas, such as the Behavioural economists layering their insights over Keynesian or Monetarist models.

The upshot is there are many schools of thought, and they often disagree. They are built on different assumptions, emphasise different mechanisms and come to different conclusions. Even though they mostly all sit somewhere between the fiscal or monetary approaches, they have competing ideas for how and even when these tools should be used.

And that raises the obvious question: how can we be told “Economists say…” by a media that knows full well how varied, contradictory and contested these schools of thought are?

The differences in economics aren’t just about the models or the schools. Over the last century, different ideas have risen and fallen depending on the problems of the time. They worked for the world they were designed for, and when the world changed, so did the theories. The old theories were pushed aside to make room for new, but often their core ideas were often absorbed by the newcomers.

In the early 20th century, Classical economics dominated, until the Great Depression exposed its limitations. Then Keynes arrived with The General Theory of Employment, Interest and Money, and for the next 30–40 years right through the Second World War and the post-war boom, Keynesian thinking shaped almost every major economy.

But other economists were quietly building their own frameworks. The Chicago School developed from the 1950s onward, gaining influence in the 1970s as inflation surged and Keynesian tools struggled. From this grew the New Classical and monetarist ideas that have shaped the last 40–50 years: a model built on markets, rational expectations, inflation targeting and a heavy reliance on monetary policy.

The point here isn’t to give you a history lesson. It’s to show that economic frameworks change, develop and eventually run out of road. When one school dominates for long enough, its weaknesses become visible, and in the background, the next generation of ideas is already taking shape.

My view is simple: the policies that have guided the last half-century haven’t failed, but they have run their course. A shift is coming, and several competing schools of thought are already positioning themselves to shape whatever comes next.

That shift can be seen in the media, especially social media, now frames the last 40–50 years. We hear constant claims that “capitalism has failed”, that policies have made us poorer, that everything is unaffordable. There is a grain of truth in this, but not in the sweeping macro sense it’s presented. We are measurably better off in our standard of living now, compared to the 70s. We spend money on things our parents would never have imagined: eating out regularly, multiple holidays, personal technology, streaming entertainment. Even spending half an hour’s wages on a coffee would have been unthinkable to them.

So, saying the New Classical model/Neoliberalism “failed” is lazy sloganeering. Yes, it has its flaws, but the successes are impossible to ignore. It delivered sustained growth, lifted billions out of poverty worldwide, stabilised inflation, expanded global trade, and drove extraordinary innovation and efficiency. Combined with globalisation, free trade and reduced barriers to trade, the world is a wealthier place all round.

Not that it hasn’t had its problems, or that everywhere benefitted equally. Many of the problems we see today owe as much to globalisation and the technological advances as they do to policy: automation, the offshoring of our industry, the dominance of financial markets all reshaped markets and towns in ways that weren’t fully expected or understood. So, after 45 years of the neoliberal era, we face a widening wealth gap, stalling globalisation, recurring financial crises, unaffordable housing, and the return of inflation. It’s quite a list.

I’m starting to see several social media memes and posts, and some news articles claiming the failure of neoliberalism or the collapse of capitalism. But they haven’t failed; the world just changed faster than the current model could adapt. What worked in the 1980s isn’t designed for the problems we see today. Back then, inflation was the defining issue, globalisation was just kicking off, and technology was increasing our productivity while lowering costs. This is not the landscape we see today.

We have declining productivity, an ageing population, housing shortages, strained public services and infrastructure and environmental pressures. All combined with a growing public mistrust in the very institutions that are meant to address these problems. These are not problems that can be fixed by a tweak of the interest rate or that the markets will self-correct. They will require a fresh set of tools.

This is why we are beginning to see other schools of thoughts gaining attention in the background. Modern Monetary Theory has been gaining some support; new Keynesianism ideas gaining influence, behavioural and inequality focused economic approaches are becoming more prominent. I suspect the eventual answer will sit somewhere in the middle, taking elements from several ideas and theories rather than just one. Whether they will provide the right solutions is yet to be seen, but perhaps they will for a while, just as previous models did.

And this is the point so often missing from the headlines. Economics isn’t a priesthood with one doctrine, it’s a set of competing ideas, each useful in the right circumstances and limited in the wrong ones. When the world changes, the tools must change too. Yet the media still talks as if there is one unified economic view, as if a single sentence can summarise a century of disagreement. It can’t. And that’s why “Economists say…” is almost always a red flag for a far more complicated story.

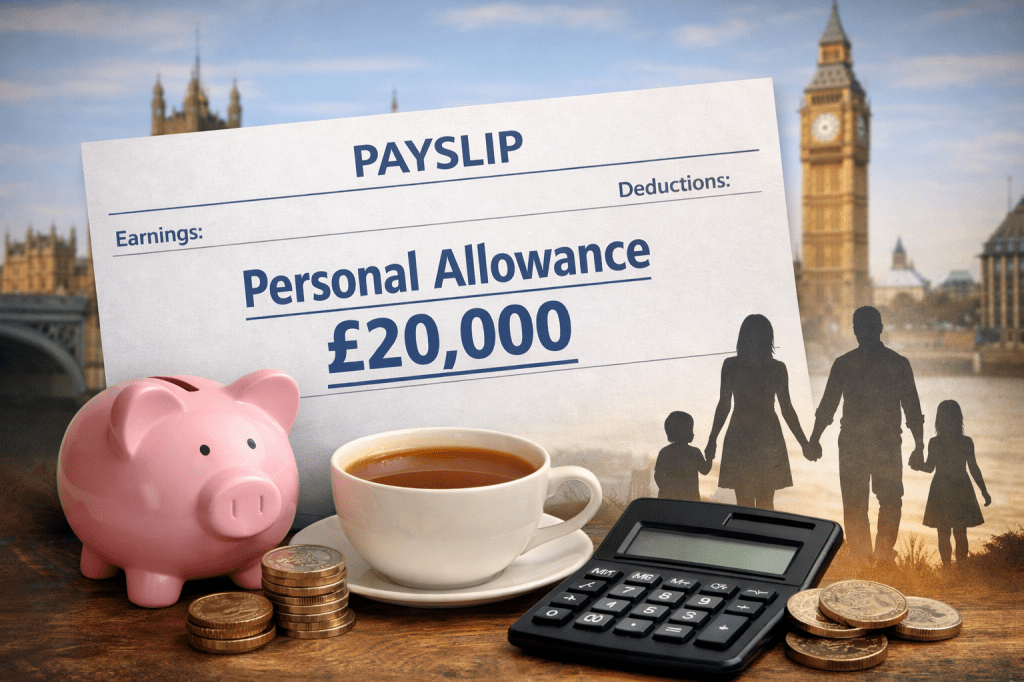

We’ve seen this problem very clearly in the way Brexit has been discussed. The now-familiar claim that it created a £90 billion ‘black hole’ in the UK’s finances is not a settled fact, it comes from one of the more pessimistic economic models produced, based on a very specific set of assumptions. Other models produced far smaller figures, and some showed entirely different sectoral outcomes. Yet one number was chosen, repeated, and presented as though it were an uncontested truth. That isn’t how economics works – that’s how narratives are built.

So, when you hear

“Economists say…”,

just remember, Economics is not a settled doctrine. It has many ideas coming from different perspectives; it evolves, argues, fractures and reforms. It shifts because the world shifts, it has in the past and will do again.

Leave a reply to kenlaidlaw Cancel reply